What We Need, A Bigger Calorie Count Can’t Provide.

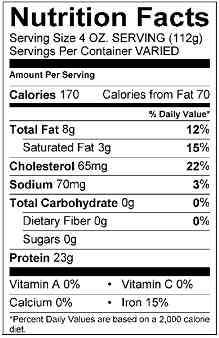

Much has been made this week of the changes that are coming in the world of nutrition labels. There have been more articles and blog posts on the internet than I think I could ever read, debating the merits of the various accepted revisions: more accurate portion sizes, larger calorie information, the removal of mandatory Vitamin C and A counts in favor of mandatory potassium and Vitamin D counts, and the addition of an “added sugars” line item to help people differentiate between naturally occurring sugars in their food and the sugars that are added during processing.

Much has been made this week of the changes that are coming in the world of nutrition labels. There have been more articles and blog posts on the internet than I think I could ever read, debating the merits of the various accepted revisions: more accurate portion sizes, larger calorie information, the removal of mandatory Vitamin C and A counts in favor of mandatory potassium and Vitamin D counts, and the addition of an “added sugars” line item to help people differentiate between naturally occurring sugars in their food and the sugars that are added during processing.

I’ve thought a lot about whether or not I’d post my own views on the nutrition label changes, and what I’d say if I did. What I think I really want to say is that I don’t care much about the labels. You might think it’s because I’m going to tell you that labels aren’t required for whole, real foods, which is true; but that’s not exactly where I’m headed, because honestly, there are packaged foods in my house, as I’m sure there are in yours. Packaged foods are a reality, and likely a permanent one. There’s no point in arguing that they shouldn’t be here – it’s a myopic way to look at things. Better to improve the labels, I guess, than to simply try to ignore the existence of the products.

No, I don’t care about the labels because no matter how much we improve the labels, there’s a very important function that they cannot serve. It’s one I think is sorely missing from our current society and our national dialogue about nutrition. It’s the one that I believe could be the single biggest game-changer in reversing the health fortunes of much of the Western world, and it’s not going to come from making either a font size, or a portion size, bigger. What we are lacking, what the nutrition label cannot provide, is education.

Why we insist on continuing to tweak the presentation of information to people, without also launching a large-scale effort to help them understand and use that information, is beyond me. Nutrition labels strike me the same way my son’s math homework struck me last week: It’s like we’re putting a Venn Diagram in front of a 1st-grader, expecting him to then extrapolate information from that diagram and answer word problems, without having first shown him exactly what a Venn Diagram is and why it’s useful. We’re telling people how much added sugar is in their cereal, but we’re not accompanying that information with a big push to tell them how much added sugar is considered “okay,” how that cereal fits into their entire day’s eating, why excess sugar may not be a great idea for their long-term health, and what they could choose instead of the cereal to be better off in the first place.

Yes, some of us already know those things, and we know where to find the information we seek even if we aren’t sure of the facts sometimes. But I think when you’re working with something as basic and fundamental as the labels on food, you’ve got to make sure that you’re teaching to the baseline – that everyone, regardless of their education level, interest in nutrition, or income level, can meaningfully use the information on those labels to make better choices and improve their quality of life and health. And unfortunately, “MyPlate” isn’t going to do it.

What’s really at play here, I think, is that nobody – including, and maybe especially? the government –knows exactly what to say in educating people about their food. There are as many theories about healthful diets as there are packaged foods on the store shelves, and very little consensus. One thing that seems to be latched onto over and over again is the issue of calories (hence, the BIG calorie counts on labels) – but that’s not a very encouraging, or very meaningful, place to begin a real life-changing, food-habits-changing dialogue.

We know that mathematically, “calories in, calories out” should work. We also know that it doesn’t, usually, and that’s something of a puzzle. Many people have extrapolated that to mean that “not all calories are equal.” Fine, but which calories are superior? Talk to five different “experts” and you’ll get five different results. In the meantime, according to an informal survey the “Today Show” conducted, over 40% of people ONLY look at the calories on a nutrition label. Other popular answers in that survey, by the way, included looking at markers like fiber and protein. Some people said they looked at the fat or sugar content.

Guess what wasn’t even an answer? The ingredients. Which, if you’re curious, is the only thing on a food label that I currently consult.

Now, just because that’s my personal preference doesn’t mean that it’s the “right” way to approach things. But I came down on the side of “ingredients” for a couple of reasons:

1) That whole thing about “whole, real foods?” Yeah, it’s valid. So I look for the least-junky ingredients I can find; and

2) I care so deeply about whole, real foods and un-junky ingredients because I truly believe that processed foods with the “right” calories and fat and fiber and so forth are making people sick.

I believe that so fully because personal experience tells me it’s true – at least, it’s true for me, it’s true for members of my family, and it’s true for friends of mine. Case in point: When I was in graduate school and then first out on my own in the adult world, I ate “healthy.” I prided myself on my ability to cook, and I worked hard to make “smart choices” at the grocery store. At that time in my life, I was reading nutrition labels for the calories and fat, not looking closely at ingredients. I ate lots of packaged oatmeal – a special kind that was labeled specifically for women and specifically for optimal weight management and nutrition benefits – and “heart healthy” yogurts and salad dressings. Sure, lots of my food was made with real, whole ingredients, but a significant portion of my day’s intake either came directly from, or was doctored with, “healthy” items that contained low calorie and fat counts.

Sometime during those years, I started having hormonal migraines every month, as well as low-level headaches several times a week. I also developed a funny pale-brown, almost mocha-colored spot on the side of my neck. I thought it was a recurrence of a minor, benign skin condition I’d had before, and used the same simple home remedy to get rid of it – but it didn’t go away. Of course, it also didn’t itch, hurt, or bother me in any way, so I totally forgot about it.

Years later, after having the kids, our eating habits had markedly improved. In everything I’d learned about food and nutrition because of our boys and their needs, the concept of “low fat” and “low calorie” packaged foods was essentially vilified. I’d gotten rid of my oatmeal packets, convenience dressings, grab-and-go soups, and yogurts, along with a host of other items. And the darnedest thing happened. One day, I realized that the spot on my neck was almost completely gone. It had just vanished. I also hadn’t had a hormonal migraine in months, and the only low-level headaches I’d had were easily attributed to back or eye strain. Minor discomfort was no longer a near-daily condition.

What frightened me was finding out, quite by accident, that the brown spot on my neck had most likely been the manifestation of the beginnings of insulin resistance. What?!?!? I’m no stick-thin model, but I wasn’t ever dangerously overweight. I didn’t eat tons of sweets and white carbs. I didn’t drink soda. What I DID was follow mainstream nutrition advice, and religiously seek “health” by looking at the fat and calorie counts on nutrition labels. Of course, since nobody told me that I ought to be reading the ingredients and paying attention to sugars and other additives, I had no idea that I was really pumping myself full of sweeteners and fillers every day. I very nearly paid a high price for that mistake.

Now, in ONLY reading ingredients and eating a highly whole-food-centered diet, I’m so much better off than I was in those days – no headaches, no brown spot, no food cravings, no insane monthly bloating, the list goes on and on. In reading ingredients and sticking to mainly whole foods, we were able to track down P.’s mysterious allergy to food dyes and preservatives, and totally reverse a whole host of scary and dangerous health issues for him. Our food philosophies have resulted in lower pain, fewer colds and illnesses, better energy, more stable moods, and better sleep for every single member of our family. We never would have gotten to this place if we had kept up our diligence in following the “recommendations” and the nutrition labels’ focus on fat, calories, and isolated nutrients.

I’m not blaming the labels – after all, if I’d known what to look for and how to use the information, it would have been a whole different ball game. But isn’t that the point? We’re still focusing on the wrong things when we focus on how to make the labels better. We’re making the information bigger and we’re changing WHICH facts we offer, but we’re not figuring out how to best communicate why those facts matter. Until we do that, we’ll still be a nation of calorie-counters with chronic health issues because our nutrition, ironically, is thrown totally out of whack by the efforts to improve it. We’ll still be a largely undernourished and overfed population with a weight obsession and a distant relationship to food. Calories and potassium levels are instruments of distance. Smell, taste, feel, and cooking knowledge are relational. And they’re real.

Until we have some consensus about what actually constitutes a smart, proactive, balanced way to relate to food – and an approach that universally results in better long-term health outcomes for people – our dabbling with nutrition labels won’t, I’m afraid, amount to much. It’s not a bad thing to do; it’s just a teeny little drop in a very large bucket. What a nutrition label can’t do is teach people how to listen to their bodies, or how to select and cook and enjoy food that doesn’t need a label. It can’t teach an entire population how to be really nourished by food, not just sated by convenience. It can’t put all of its own numbers and symbols into context, or draw the deep connections between its facts and someone’s ongoing health challenges. A nutrition label, even an improved one, is still just a label. We’ve got much farther to go than that.

I can think of two packaged convenience foods most people have in their homes, even if they’re pretty adamant against boxes and bags: pre-made bread and pasta. People blink at me when I point out that many brands of bread contain HFCS.

An excellent point! I admit to the pasta, but we do try to make our own bread as often as we can, preferably from traditionally fermented sourdough. It’s healthier all around that way (and keeps our consumption of bread low!).